Houston We Have a (Virtual) Problem

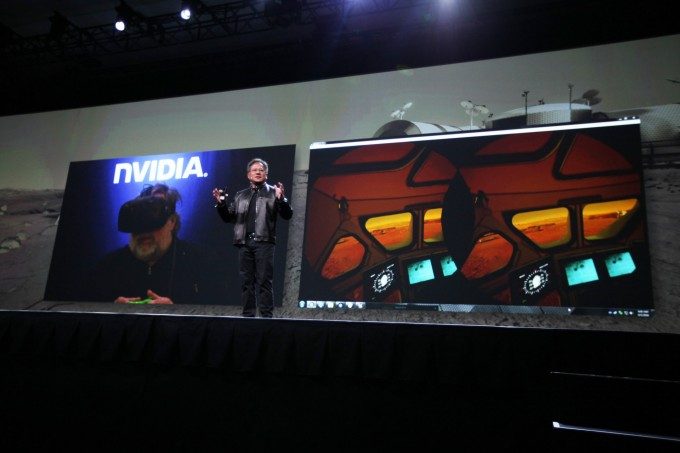

At GTC 2016 last week, NVIDIA showed off Mars 2030 during the event’s opening keynote. On stage in front of several thousand GTC attendees, NVIDIA CEO Jen-Hsun Huang introduced the experience as a detailed recreation of the surface of Mars. To drive his point home, he invited (via video feed) former Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak to be the first human to set foot on (virtual) Mars.

Donning an HTC Vive and stepping into the rover inside Mars 2030, Wozniak began to maneuver around the Martian landscape. The sequence went on for a few minutes and on more than one occasion, Wozniak said he was feeling dizzy—basically the last thing a VR developer wants to hear during a public demo of their work, let alone one being watched by several thousand people.

For the record, I felt little to no nausea during my time in Mars 2030, which surprised me given that it implements a standard twin-stick FPS control scheme, which is known as potentially dizzying to some (myself included). I asked Julian Reyes, Fusion’s Lead VR Producer who is spearheading Mars 2030, how he felt about Wozniak’s reaction.

“At first I don’t even think he was quite familiar with what he was about to get into, because he grabbed the controller backwards,” said Reyes. “We wanted to leave it at a state of spontaneity and so he had no idea what he was walking into as soon as he put the headset on… at least on our end, we’re hitting the framerate at 90 FPS. Maybe some of the motion of being able to drive the rover sideways [a feature of the rover prototype] could have made him a little bit dizzy… none of the people who I’ve seen try it get dizzy.”

“I think that breaks immersion,” Reyes told me when I why Mars 2030 doesn’t use any tricks like snap turning or blinking to improve comfort in VR for people like Wozniak.

Given what Fusion has managed to achieve in Mars 2030, it would be a shame if comfort alone was a limiting factor in how many people get to enjoy it. With many months remaining before launch, Reyes and his team may implement such options yet.

More Than a Tourist

So what do you actually do in Mars 2030, other than being occasionally overcome with the feeling that you’re actually standing on another planet? I got a look at an early mission among several you’ll be able to undertake during your time on the Martian surface.

Starting at the base, my task was to explore an immense lava tube. It wasn’t terribly far from the site, but certainly too far to walk. Luckily there’s a rover parked at the base—identical to a prototype that NASA is considering sending to Mars; I hopped inside and began following a waymarker toward the lava tube. The path spiraled out from the base location and took me through surprisingly volatile terrain.

[gfycat data_id=”GlaringHighlevelBedlingtonterrier” data_autoplay=true data_controls=false]

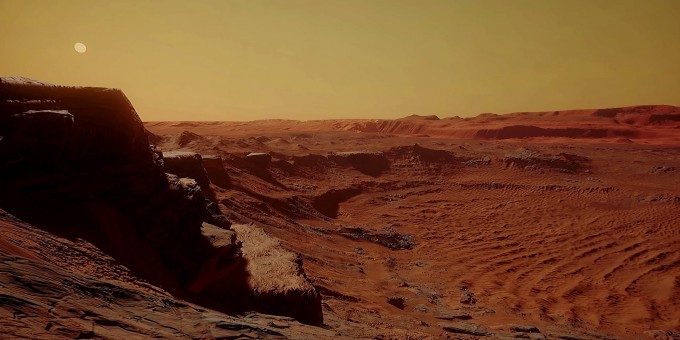

Prior to being on the Red Planet via Mars 2030, I had only ever seen surface photos of Mars taken by robotic rovers. These generally showed the rovers in the middle of a big, flat, rocky desert, and that’s all I knew Mars to look like. Yet here, as I drove the rover from base, my perspective of Mars was completely rewritten as I realized for the first time ever just how harsh the planet’s terrain could be.

“NASA doesn’t necessarily target areas that might be a little more dangerous for the [robotic] rover, but all of [the big formations show] up clear as day on satellite,” Sonnekalb said. “Because you have a third of the gravity, mountains don’t settle as much and you get these ridiculously deep canyons and high mountains.”

I wound through gulleys and climbed steep inclines as I followed the trail set before me. After a few minutes of driving I emerged from a small valley to see a positively massive crater that stretched out what seemed to be at least a mile in front of me. My path would take me straight down the side of the crater; as I drove I couldn’t help but peek out the rover’s window to stare in awe at what had formed within the crater: huge, rippling hills showed evidence of Mars’ once highly active geologic processes. Knowing that what I was looking at were actual features of the Martian landscape, briefly brought back that feeling of actually being on the planet.

As I reached the end of the mission path, I exited the rover standing before a positively massive cavern—a lava tube, to be precise—that seemed wide enough for a plane to fly through. I had absolutely no idea that such features existed on Mars, and even if I had, I would have never guessed they’d be so huge. And yet here I was, peering inside of this massive natural formation—one that NASA may actually send people to explore one day, following the same virtual path that I took to get here.