Backed with support from NASA, the development of Mars 2030 is underscored by a singular mission: do everything possible to make the player feel like they’re actually on Mars. And that, apparently, means starting with a massive, detailed recreation of an actual part of the planet’s surface.

I’m fascinated with space, and by extension, Mars. I’ve seen Mars through a telescope. I’ve shot amateur astrophotos of Mars. I’ve looked at topographical maps of Mars. I’ve even gazed upon the real surface of Mars in VR, from a panoramic photo taken by the Curiosity rover and viewed through Gear VR.

But it wasn’t until Mars 2030 that I felt, however briefly, that I was actually standing on Mars.

It’s incredibly hard to describe, but anyone interested in space surely knows the feeling; that fleeting moment where for just an instant, you grasp the absurd scale of the cosmos and your minute role within it. If there’s a name for the feeling I do not know it, but I do know that I can occasionally invoke it with a video like this, and I also now know that Mars 2030 has the same power.

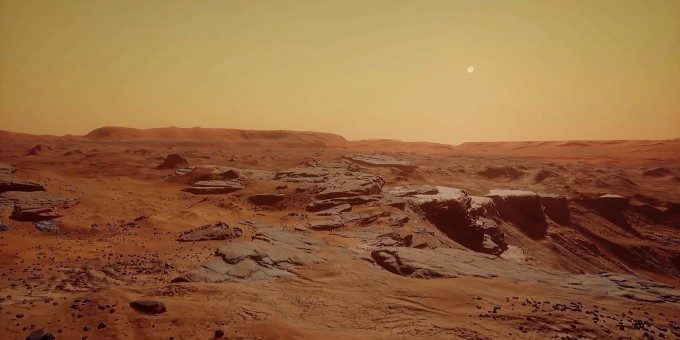

The feeling came when I was standing atop a rocky outcropping not far from the white capsule-shaped habitat that functions as a sort of home base in Mars 2030. As I raised my head to take inventory of the landscape, stretched out before me I saw boulders, valleys, and lowlands which eventually ended hundreds of kilometers away in a massive mountainscape. Above that was the Sun, but unlike I’d ever seen it.

At about 40% as bright as the Sun seen from Earth, the Sun on Mars looked smaller and felt more distant. About 20 degrees above the horizon, it was tinted a faint red as its light passed through the thin Martian atmosphere. It was at this moment—staring at the Sun and the realistic way it reflected from the landscape—that the feeling washed over me: this is what the Sun would look like if I was actually standing in this spot on Mars. In that moment I felt further away from the Sun than I ever have here on Earth… and that made me feel like I was actually standing there on the Red Planet.

But it didn’t last long… it never does; no matter how long I try to cling to that space-induced feeling of awe, it’s but a ghost passing through me. Still, the fact that I felt it at all meant that developer FUSION Media had achieved what they’d set out to do with Mars 2030.

“We want you to feel like you’re standing on mars,” said Justin Sonnekalb, a game designer working on the Mars 2030 project. “We want you to feel like you’re actually there.”

Making Mars

To give players the feeling of being on the planet, the team went to the group that knows Mars best: NASA. The space agency agreed to collaborate on the project, opening an official channel to share technical expertise and “the results of ongoing studies on space transportation systems, concepts of operations, and human health and performance,” wrote NASA in the announcement of the project late last year. “While still early in formulation, this partnership makes possible the first virtual reality Mars surface experience using actual operational and hardware concepts that NASA and MIT are studying today.”

Mars 2030 doesn’t just look like Mars, it’s a recreation of an actual region of the planet with a player-accessible area of 20 sq km, about the size of Skyrim (2011), Sonnekalb told me. The total visible area, which includes the distant mountains that I saw, stretches much further… more than 700 km of real geometry from one size to the other.

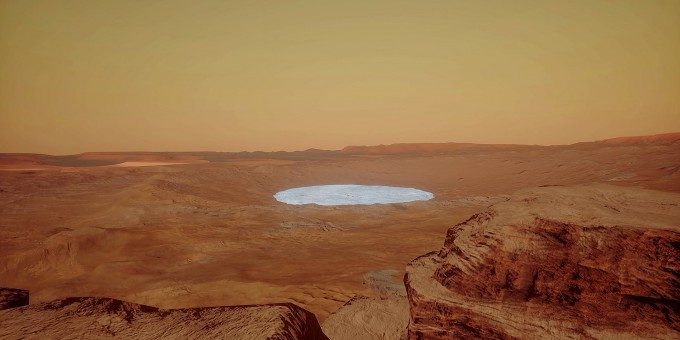

To create this plot of Mars, Fusion borrowed measurements of the planet’s surface from NASA. The player-accessible space is based on topographical data that’s sampled every meter and is accurate to within 30 cm of the actual elevation. The larger visible area is based on data from the Mars Express orbiter, sampled every 50 meters with accuracy down to one meter, Sonnekalb said.

With the data in hand, the team set off to create the space, but it takes more than topographical data alone to make a compelling recreation of an actual planet.

“Our lead environment artist actually worked with a NASA geologist to find the correct reflectance factors to really get the materials to be as photorealistic as possible,” said Sonnekalb. “We use UE4’s physically-based rendering for everything.”

The scale and visual fidelity of Mars 2030 is something never done before in VR, says NVIDIA’s Zvi Greenstein, GM of GeForce Desktop, who has been working closely with Fusion on the project.

“You basically have the real Martian terrain… the real topography with rocks… the lightning model is accurate, the gravity model is accurate… the development team recorded the actual sound from the rover,” Greenstein told me. “The rover, the habitat [modules], the labs… whatever you see in this application is based on actual CAD models provided by NASA…”

The development team is building Mars 2030 from as much real data as they can, and they are highlighting that attention to detail by designing for the absolute upper-tier of enthusiast graphical hardware: dual NVIDIA GTX 980 Ti GPUs.

“We’re pushing 50 million polygons per frame,” Greenstein said, though he also mentioned that they plan to scale things down so that the experience can still run on more common VR hardware like the GTX 970.