Both the Rift and the Vive first launched to consumers around this time two years ago, but their debut, and the games that launched alongside them, were the culmination of years of prior game design experimentation in a new medium that brought both new opportunities and challenges. Cloudhead Games, developers of Vive launch title The Gallery: Call of the Starseed, were among those leading the charge. On this occasion, the two year anniversary of modern VR headsets becoming available to consumers, the studio’s Lead Programmer, Paul White, and Narrative Designer, Antony Stevens, look back at the studio’s journey in VR development and where it has led them today.

Guest Article by Paul White and Antony Stevens

Paul is the Lead Programmer at Cloudhead Games. Bitten by the VR bug in the early 90s, Paul has been programming since fifth grade. With Cloudhead Games, Paul has more than five years experience in modern VR research and development, producing award-winning tech for The Gallery VR series.

Antony is the Narrative Designer and Community Lead at Cloudhead Games. With Cloudhead since the launch of consumer VR in 2016, Antony has helped shape and share the stories of its developers across multiple mediums, including in The Gallery: Heart of the Emberstone.

The First Climb

Fall 2013, Oculus DK1 + Razer Hydra

My journey into VR locomotion began with the sunsetting Razer Hydra in late 2013. An early motion controller system tracked by a low-power magnetic field, the Hydra was originally designed as a peripheral for flat PC gaming. But for some of us, it was also an unlikely hero—the Hydra was the first big key to unlocking presence in virtual reality, thanks to its positional tracking

It was the era of the DK1, the first of the Oculus Rift prototypes available to Kickstarters, offering only rotational head tracking during its initial foray into the rebirth of VR. Without positional tracking of the head or hands, player movement in VR projects was either bound to the analogue sticks or omitted entirely. These were the standards and limitations of the time; VR as we know it today was yet to exist.

I was working on Exploration School, an early tech demo for our built-for-VR adventure game The Gallery (2016). My challenge was to use the Hydra to mimic the motions of climbing a wall without using control sticks—just reach out and grab it. It sounds straightforward now, but during those early days of VR we thought it could never be done with the available tech.

Holding the wired Hydra, you would reach out with your hand and press a button to capture the position of that arm on a surface. Any motion you made next would be countered and represented in game with our body persistence. If you let your arm down, your position would counter that movement, causing your camera and in-game body to move upward. If you raised your arm up, your position would counter, and you would climb down. It felt intuitive, all tech considered.

VR devs all around were experimenting with anything and everything, from climbing to flying to roller coasters, but there was no substantial test audience. Motion sickness was a concern internally, but there weren’t enough headsets in the wild to know how widespread its effect was. We knew what artificial movement felt like to us and other developers, but there was no way to know what was working and what wasn’t for various sensitivities.

When we brought Exploration School to public events, we gave players the best advice we had for avoiding motion sickness: “Don’t look down.”

The Bigger Picture

Spring 2014, Oculus DKHD + Razer Hydra

Those first two years saw many VR developers building single-room projects—playboxes with no need for travel or locomotion. The Oculus Rift, for all intents and purposes, was a seated experience. Our project, The Gallery, was a larger world that needed exploration, with terrain that was organic and rugged. We wanted realism where you could walk around, look at things, and feel alive in a world. VR was predominantly blocky at the time (both graphically and otherwise), and walking with the analogue stick felt like your body was a cart behind you, changing direction to chase after you each time you turned your head. It all felt unnatural.

‘Tank Move’ was one alternative. This method allowed your head to deviate from the direction you were moving, so you could pan your view around an environment completely decoupled from your body direction. Think of your head as a swiveling neck turret, while your body is driven on tracks and controlled by a joystick. It was a fitting abstraction.

Tank Move was better because it meant you could look around while you moved. It was also worse because of vestibular disconnect—motion sickness caused by your brain perceiving directional movement through your eyes (the headset), without physical motion detected by your inner ear (the real one). Decoupling head movement from the body could ultimately decouple stomach contents from the body as well.

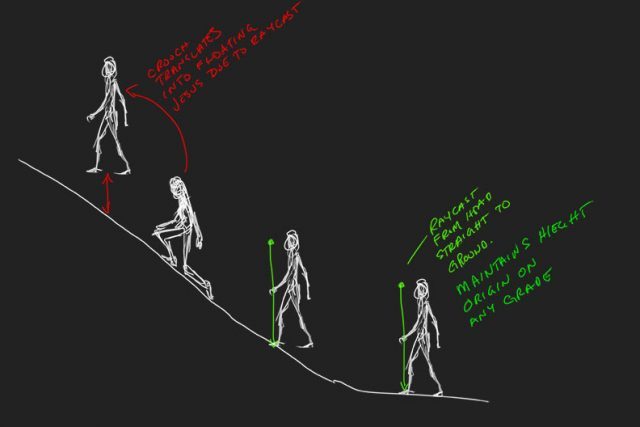

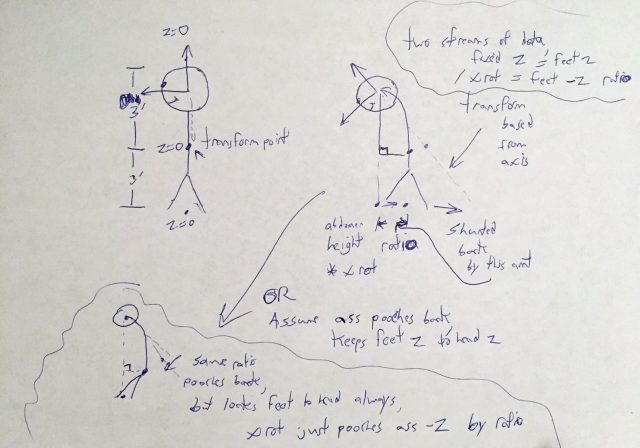

More important than the freedom to look around was the freedom to move around, and we knew that the positional tracking features of the upcoming DK2 (and experimental hardware from Valve) would help dictate movement. In the meantime, we wanted to get ahead of the curve and start building for the future that VR was heading toward. Using heuristic spine modeling and a simulated height, I was able to turn the single, rotational tracking point of the DK1 into two positional tracking points: head and root.

With that inferred root, we then had the approximate location of the player’s torso in relation to their head, and could then adjust their body avatar with movements accordingly. We could tell the difference between natural displacements, from the player crouching into a tent, to peering over a balcony at the distant world around them.

In the end, the feature never made it in. Everything was about to change anyway.