As of October 25th, Facebook Spaces has been shut down to “make way” for the company’s next try at a social VR platform, Horizon. While Spaces didn’t catch on, it represented some of the company’s finest VR design work to date. Facebook would do well not to forget its lessons.

Spotted by UploadVR, this week marked the end for Facebook Spaces, the company’s attempt to bring the Facebook experience into social VR. A message on the official website makes clear that Horizon, which Facebook showed off last month, is the new social VR priority for the company.

While the platform didn’t achieve traction, it was one of the most thoughtfully designed VR projects to come from Facebook. Not to say that it did everything right; Facebook Spaces was in equal parts a great example of what to do and what not to do in social VR.

A Deeply Spatial Interface

While many VR applications are still struggling to get away from the dreaded laser-pointer interface, Facebook Spaces was built from the ground up for spatial interactions. Just about everything you do in the application happens with a combination of touching and grabbing things within arms reach. This is a great place to start for any social VR application because spatial interaction naturally lends itself to social interaction, in the form of exchanging and collaboratively interacting with meaningful objects.

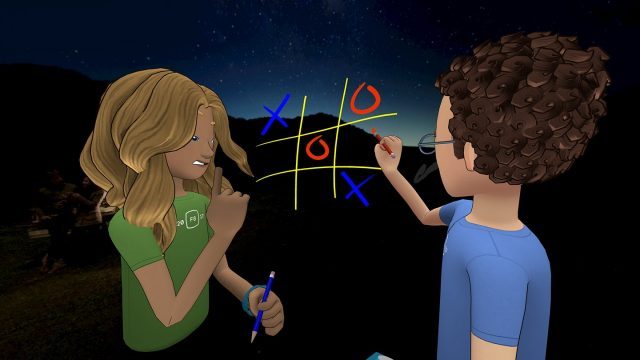

A spatial interface is that much richer when virtual objects are persistent and everyone can participate. Spaces encouraged this sort of interaction from the get-go by allowing anyone in the room to interact with the objects around them. Not only does this create a strong sense of social embodiment, but it’s also conducive to deeper emergent behaviors, like users drawing their own board games for everyone in the room to play.

A Meeting Place, Not a World

Many social VR applications try to do too much at once and lose focus on the value of simply communicating with someone you care about. Games like Rec Room are plenty of fun in their own right, but their complexity means they aren’t a great place to simply be face to face with another person—in the same way that a theme park is a much worse place for catching up with an old friend than a pub.

Facebook Spaces had the excellent idea of not building a world for people to explore, but instead focusing on discrete rooms with features built to facilitate genuine human communication. It did this by using the concept of a ‘table’; a table is a thing which people who know each other gather around, and atop which they share things that are meaningful to them.

The table concept wasn’t just a good social metaphor, it was also a useful design principle. Rather than popping into a big virtual world with miles to roam, Facebook Spaces puts you directly in a seat at the table. This achieves a few things, notably: automatically spacing users at a comfortable ‘social proximity’ while preventing them from accidentally getting uncomfortably close.

I can’t count the number of times I’ve been in other social VR applications and been engaged in a meaningful conversation only to have it interrupted by one of the participants accidentally teleporting 20 feet away (or worse, into my body). If the goal isn’t to explore a virtual world, but simply to facilitate meaningful communication between people, open-ended locomotion is nothing but a distraction and an invitation for immersion-breaking accidents which kill social momentum.

A Direct Line to the Outside World

One of the absolute coolest parts of Facebook Spaces, and one which still has no equal, was the ability to initiate a Messenger video call to friends in the real world. You’d start a video call in VR and your friend would get a ring on their phone in. When they answered, they’d see your avatar and everything in your Facebook Spaces room, while you’d see them in RL through their camera. You could even pull the video window up to the virtual table and your friend could see everything and participate in the conversation.

It was an incredibly novel and interesting way to share VR and avoid a feeling of isolation; after all, if Facebook Spaces only allowed you to communicate with friends who owned a VR headset, it wouldn’t be very inclusive….

If It Isn’t Inclusive, It Isn’t Social

While the ability to video call friends in real life was a great way to make social VR feel open to everyone, this was betrayed by other choices which hampered the adoption of Spaces. One of the key lessons that Facebook needs to learn if it wants to build a genuine social VR platform, is that it needs to be inclusive of the entire VR sphere.

Facebook.com (the website/app) wouldn’t be any good if it was only available on Android phones or only available on Mac. No matter what phone, operating system, or browser you use, you can be part of Facebook.com; as more of your friends join a given social network, the more valuable it becomes to you (this is the ‘network effect’, and it’s a major reason why Facebook.com dominates the social network world.

If any company in the tech space should understand this, you’d think it would be Facebook. Yet Facebook Spaces was only available on Rift and Vive. That meant the platform excluded PlayStation VR and all of Facebook’s other headsets: Oculus Go, Quest, and Gear VR. This is part of a broader issue of social VR fragmentation which has plagued the company.

What’s more, the need to be ‘Facebook friends’ before interacting with anyone in Facebook Spaces stymied use-cases beyond communicating with those you were already connected to. If you wanted to have a meeting with a business acquaintance or a tutoring session with a teacher, both parties would need to be ok with friending each other on Facebook, and then use some other communication channel to facilitate the friending of participants. It was a clunky hassle and an unnecessary barrier to getting people together inside of what was otherwise a very thoughtfully designed space for social interaction.

– – — – –

It’s my hope that whoever ultimately pulled the plug on Facebook Spaces didn’t just look at the lack of traction and say ‘this was a failure, let’s start from scratch’; there’s a ton of smart design here which would be an absolute shame to leave on the table. From what I’ve seen of Horizon—Facebook’s next attempt at a social VR platform—I don’t have much confidence that the learnings of Spaces will be put to much use, but I’ve certainly got my fingers crossed.