Recently released on the Quest store, Cubism is a spatial puzzle game with a slick minimal presentation. Designed by a solo indie developer Thomas Van Bouwel as a side project, the game impressively holds the highest user rating among all Quest apps with more than 100 reviews, according to our latest ranking. We reached to Van Bouwel to learn more about his approach to the project and lessons learned along the way.

Guest Article by Thomas Van Bouwel Thomas is a Belgian-Brazilian VR developer currently based in Brussels. Although his original background is in architecture, his current work in VR spans from indie games like Cubism to enterprise software for architects and engineers like Resolve.

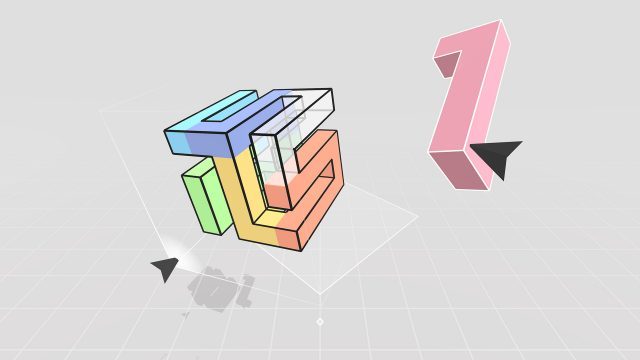

In September I launched Cubism, a minimal VR puzzle game about assembling colorful blocks into complex geometric shapes. It was my first commercial release as a game developer.

I developed Cubism on my own in my spare time, all while keeping my job as lead product engineer at Resolve, a Brooklyn-based enterprise VR start-up. I’ve only recently transitioned into working part-time for the game in the months leading up to its release.

Bootstrapping your first game alongside a full-time job can be a good way to allow for a flexible development schedule and reduce financial risk—but I think it’s only feasible if you design around your limitations and don’t over-scope your game.

In this article, I want to share some lessons I learned on how to stay on track when bootstrapping your first VR game.

1. Prototype & Playtest as Soon as Possible

The first questions you need to answer when starting any new game is: “is this fun?” and “could this have an audience?” A good way to answer these questions is to build a vertical slice—a small but fully playable segment of your game idea—as soon as possible, and put it in front of strangers to gauge their reaction.

I built the first functional prototype for Cubism over a weekend back in 2017. The prototype was pretty bare bones, but playable, and was enough for me to test the concept with friends and colleagues and to share the idea with strangers online to see if a game like this could spark interest.

The first prototype of Cubism had 3 puzzles, but no menu or game logic. Two of those three original puzzles ended up in the final game.

2. Scope Within Your Constraints

Choosing the right scope for a game is the best way to ensure you can actually finish it, and this will be determined mostly by your constraints (budget, skillset, time, etc).

For Cubism, I knew I’d have limited time to work on it, I knew I wanted to work solo to keep my schedule flexible, and I knew that things like 3D modelling, graphics programming and audio design weren’t my strong suit. Cubism’s minimal aesthetic and straight-forward gameplay leaned into these constraints, and helped inform many design decisions along the way.

For example, the minimal environment removed the need for detailed environment modelling or complex lighting, and helped put the focus on the puzzle in front of the player. This lack of environment also meant that having gravity made no sense, since pieces had no surface to fall on other than the floor—so instead, everything floats. This actually made puzzle solving a bit easier and enabled more complex puzzle shapes which wouldn’t be possible if gravity applied.

The lack of gravity in Cubism allows for more complex puzzle shapes.

Adjusting scope is something that will inevitably happen throughout development as well. One instance where I realized I was over-scoping was with my plans to support hand-tracking in the initial release of the game.

When hand-tracking first became available, I quickly prototyped experimental support for the feature and released it in a demo on SideQuest as it seemed like hand-tracking could make for a very intuitive way of playing the game. The reality was that hand-tracking at the time still had limitations, and the quality of people’s experience with it varied highly depending on their lighting conditions and their expectations of the feature. The demo I made did not handle these limitations well.

I realized that properly implementing this feature would require much more work than I originally anticipated, which would delay the release of the actual game. I instead decided to remove the feature from the release scope and plan it for a future update.

This was a difficult call to make, since the SideQuest demo set expectations for the full game to support this feature as well, but I think it was the right call as it ensured I could give the development of this feature the time it required to be done properly.

3. Build Tools That Save You Time

When you recognize that an aspect of your game will require a ton of iteration to get right, it’s worth looking into what tools you can buy or build to help make that iteration more efficient.

For Cubism, I realized early on that I would need to iterate a lot on the design of the puzzles in the game, so one of the first things I built was a simple puzzle editor. It was far from release-ready, but as a developer tool it had a huge impact on how quickly I was able to iterate and find interesting puzzle designs.

An early in-VR level editor tool helped me speed up puzzle design and iteration

Another aspect of the game that required a lot of iteration was the audio design. In Cubism, every puzzle piece is associated with a note, meaning every puzzle forms a complete chord once finished. Completed puzzles and their associated chords form a complete song. When a player presses the play button in the menu, it will play this song as it goes through all the levels they’ve solved.

Pressing the play button lets players hear a song composed of chords associated with each puzzle they’ve completed.

In Unity3D, I built a simple editor tool that would let me modify the notes associated with the puzzles and would save these notes in a separate file. This allowed me to test multiple songs for the game in parallel and made it easier for me to keep the notes associated with puzzles up to date while the puzzle designs evolved during development.

4. Don’t Playtest Your Game with Gamers (at first)

If you want to make your VR game accessible for newcomers to the medium, take special care to playtest it with non-gamers during development.

Since Cubism was meant to be a casual game, one of my design goals was to make it as pick-up-and-play as possible for newcomers to the medium. However, about a year and a half into development I realized one of the biggest blockers for newcomers was the game’s control scheme and the onboarding tutorial to teach new players.

Almost every button had a function mapped to it, and the game would start by walking you through each button, which would be very disorienting for people who weren’t used to holding controllers.

Cubism originally used every button on the controller and the onboarding tutorial would walk users though each one.

It took me a long time to realize this was an issue, because I had mainly been testing the game with other developers, gamers, and VR enthusiasts who would tend to breeze through the controller onboarding. It was only during a more family-oriented game event, where I got a chance to test the game with more non-gamers, that I realized input was a barrier to entry for some folks.

After that insight I focussed on simplifying the control scheme by making the entire game playable with just the triggers. This had some design implications as well: the menu moved from being anchored to the player’s hand to being anchored underneath the puzzle. And moving the entire puzzle, which used to be mapped to the grip buttons, now happened by grabbing the puzzle within its bounding box.

These changes greatly simplified onboarding and made the game much more easy to pick-up-and-play. Where some players used to get confused by the original tutorial, they would now breeze through it and be solving their first puzzle within 10-20 seconds of launching the game.

Cubism can now fully be played with just the triggers, greatly simplifying and shortening the onboarding tutorial.

5. Don’t Solo Dev Alone

Even though I made Cubism on my own, I would never have been able to finish the game without the support of various friends and organizations within the VR community. They kept me motivated throughout development and have given me valuable advice when I was stuck.

In most cities I’ve lived in since I started working on Cubism, I’ve been able to find meetup groups for Unity developers, indie game developers, or VR enthusiasts. And even though going to actual meetups is harder these days, many of these groups also have active online communities on Slack or Discord.

If you’re planning on developing on the Oculus platform, I also highly recommend joining their Oculus Start program. Beyond the support Oculus provides to Start developers, they also have a really active and supportive community on Discord.

– – — – –

The choice of whether or not to work solo and/or part-time on a project will likely depend on your circumstances and the nature of the game you’re making. I’ve definitely felt the downsides of solo spare-time development as well: a dev cycle that was probably longer than it needed to be, being confronted with gaps in my own knowledge when it came to actually finishing and publishing a game, or the lack of a creative sparring partner to work through design problems and help make decisions.

But for Cubism, there was a flip-side to each of these downsides as well: not having to compromise between a game I wanted to make and a job I enjoyed doing, being forced to learn new skills, and being incentivised to seek out the wider gamedev community for advice, support and motivation.

In many cases, it will make more sense to work together with others or to seek funding for development, but if you’re planning on solo-bootstrapping your first game, I hope this article will be helpful!