Researchers from Facebook’s R&D department, Facebook Reality Labs, and the University of California, Berkeley have published new research which demonstrates a method for expanding the field-of-view of holographic displays.

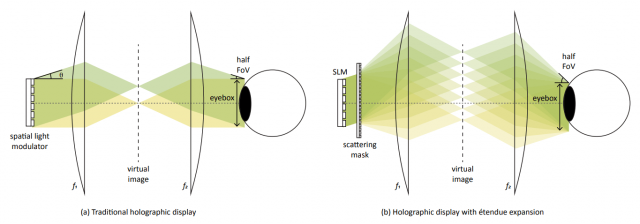

In the paper, titled High Resolution Étendue Expansion for Holographic Displays, researchers Grace Kuo, Laura Waller, Ren Ng, and Andrew Maimone explain that when it comes to holographic displays there’s an intrinsic inverse link between a display’s field-of-view and its eye-box (the eye-box is the area in which the image from a display can be seen). If you want a larger eye-box, you get a smaller field-of-view. And if you want a larger field of view, you get a smaller eye-box.

If the eye-box is too small, even the movement from the rotation of your eye would make the image invisible because your pupil would leave the eye-box when looking any direction but forward. A large eye-box is necessary not only to keep the image visible during eye movement, but also to compensate for subtle differences in headset fit from one session to the next.

The researchers explain that a traditional holographic display with a 120° horizontal field-of-view would have an eye-box of just 1.05mm—far too small for practical use in a headset. On the other hand, a holographic display with a 10mm eye-box would have a horizontal field-of-view of just 12.7°.

If you want to satisfy both a 120° field-of-view and a 10mm eye-box, the researchers say, you’d need a holographic display with a resolution of 32,500 × 32,500. That’s not only impractical because such a display doesn’t exist, but even if it did, rendering that many pixels for real-time applications would be impossible with today’s hardware.

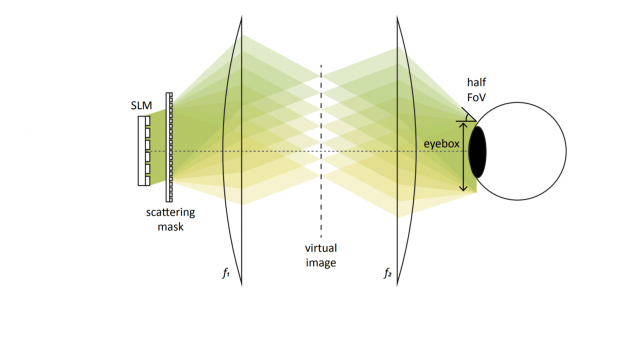

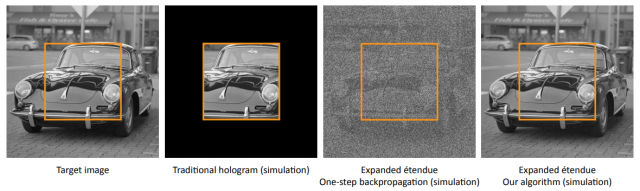

So, the researchers propose a different solution, which is decouple the link between field-of-view and eye-box in a holographic display. The method proposes the use of a scattering element placed in front of the display which scatters the light to expand its cone of propagation (also known as étendue). Doing so allows the field-of-view and eye-box characteristics to be adjusted independently.

At a high level, it’s very similar to the approach that existing headsets use to handle color separation (chromatic aberration) as light passes through the lenses—rendered frames pre-separate colors so that the lens ends up bending the colors back into the correct place.

The researchers used optical simulations to hone their algorithm and then built a benchtop prototype of their proposed pipeline to experimentally demonstrate the method for expanding the field of view of a holographic display.

Toward the end of the paper they identify miniaturization, compute time, and perceptual effects among the challenges needed to be addressed by further research.

The paper also hints at potential future projects for the team, which may be to attempt to combine this method with prior work from one of the paper’s researchers, Andrew Maimone.

“The prototype presented in this work is intended as a proof-of-concept; the final design is ideally a wearable display with a sunglasses-like form factor. Starting with the design presented by Maimone et al. [2017], which had promising form factor and FoV but very limited eyebox, we propose integrating our scattering mask into the holographic optical element that acts as an image combiner.”

If you read our article last month on Facebook’s holographic folded optics, you may be wondering how these projects differ.

The holographic folded optics project makes use of a holographic lens to focus light, but not a holographic display to generate the image in the first place. That project also employs folded optics to significantly reduce the size of such a display.

On the other hand, the research outlined in this article deals with making actual holographic displays more practical by showing that a large field-of-view and large eye-box are not mutually exclusive in a holographic display.