VR feels like it’s simultaneously moving fast and slow. It’s been two years and four months since the leading PC VR headsets, the Oculus Rift and HTC Vive, hit shelves. The leading high-end headset overall, PSVR, has only been around for one year and nine months. That’s a significant amount of time for individual products, but just a blip in the context of the formation of a brand new ecosystem and medium. Looking forward to the next generation of VR, advancements in specs and experience are not the only improvement; the industry as a whole is becoming more cohesive, which will ultimately benefit everyone involved. Here’s how.

OpenXR API Standard

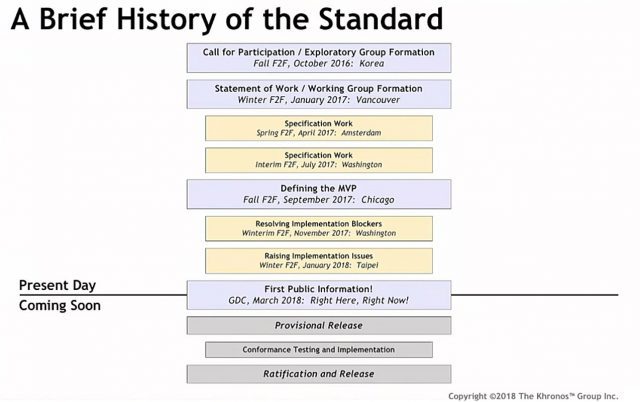

OpenXR is an in-development standard that’s open and royalty free. It’s being developed by a consortium consisting of effectively every major player in the VR market, including chip makers, headset makers, game engines, publishers, and VR app stores. The standard is being developed under the Khronos Group, the organization behind a number of major graphics standards like OpenGL, WebGL, and Vulkan.

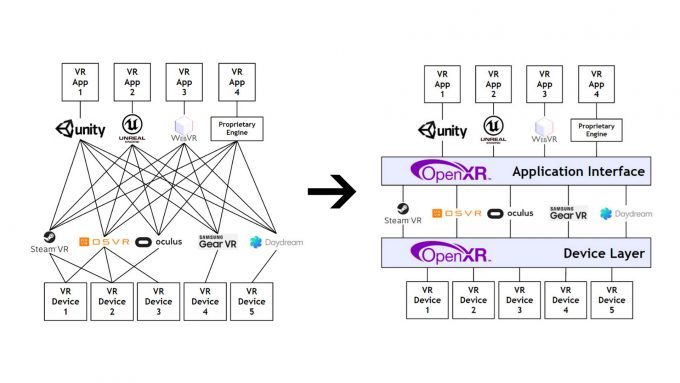

OpenXR aims to foster greater interoperability between major pieces of the VR ecosystem: apps, game engines, and headsets. The goal is to make it easier to ‘write once and run anywhere’, meaning reducing the redundancy and complexity for an app, game engine, or headset to support the multitude of options available on the market.

The OpenXR project is building an ‘Application Interface’, which sits between VR apps and content platforms, and a ‘Device Layer’, which sits between the content platforms and individual VR headsets and devices. The idea is that the Application Interface and the Device Layer should be standardized so that everyone can design against a common target rather than needing to maintain individual support for many different platforms and devices.

Hypothetically this means that a game supporting OpenXR that launches tomorrow could work with an OpenXR-supported headset that launches in five years, since both were built targeting the same Application Interface and Device Layer. Similarly, a OpenXR headset from one company could work with OpenXR controllers from another company, letting users use various devices together more easily.

Similarly, if a new game engine wanted to offer support for VR, it needs only to target the OpenXR Application Interface to potentially work with every headset and VR platform that supports OpenXR.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that every VR platform that supports OpenXR will support every headset that supports OpenXR (for instance, the HTC Vive on the Oculus Store), but it does mean that the technical capability is in place if platform stakeholders want to move to an open device approach.

In total, this makes it easier for new players to jump into the VR market, whether that be with a game, a game engine, a content platform, or even a new headset or accessory. This benefits everyone in the market by creating more options for developers and customers, and fosters competition which leads to better products.

In March this year, the OpenXR group announced its latest progress and did a deep dive into the technical scope of the OpenXR spec. While the group hasn’t announced an official release of the standard, the latest timeline shows that they are nearing an initial release, which we expect could come by the end of the year.

VirtualLink Connection Standard

Most major tethered headsets today require two or three plugs on the end of the cable which need to be connected to the host PC, and they differ from one headset to the next. The Rift, for instance, has one HDMI plug and one USB plug. The Vive has one DisplayPort plug, one USB plug, and a separate power plug that needs to connect to a wall outlet.VirtualLink, backed by most of the major players in the VR industry, is a newly announced connection standard that aims to simplify headset plugs into a single, well specified connector.

Based on USB-C, the VirtualLink connector offers four high-speed HBR3 DisplayPort lanes (which are “scalable for future needs”), a USB3.1 data channel for on-board cameras, and up to 27 watts of power. The standard is said to be “purpose-built for VR,” being optimized for latency and the needs of next-generation headsets.

The new connector will not only simplify the connection on the end of the headset’s cable, it will also make it easier for customers to understand if a given computer will support a certain headset, which eases the process of buying a VR Ready system.

Whereas today you might think your system meets all the specifications for a VR headset, only to find that your USB ports don’t actually support the speeds required for the headset, or you don’t have the right HDMI spec, the VirtualLink standard means that both customers and headset makers can count on the connector to support a well specified set of capabilities.

VirtualLink was just announced last month and is expected to debut with the next generation of GPUs and PC VR headsets; the former we could see by the end of the year.