Originally released on Macintosh in 1993, Myst immersed players in a first-person adventure that was truly ahead of its time, both visually and conceptually. Real-time 3D rendering was still in its infancy back then, so there was something unique about Myst’s rich pre-rendered environments and its simple (but effective) story, which was told across 2,500 point-and-click stills. Cyan, the same studio who help pioneer the adventure game genre with the original Myst, have now rebuilt the game from the ground-up for traditional monitors and VR headsets, launching first on Oculus Quest. Peeling back the nostalgic sheen, it’s clear there’s still something special about Myst, although it’s undoubtedly a product of its time.

MYST Details:

Available On: Oculus Quest (SteamVR release TBA)

Release Date: December 10th, 2020

Price: $30

Developer: Cyan

Reviewed On: Quest 2

Note: My first and only encounter with Myst was in the mid-90s, and I never finished it as a kid. Much of the game is completely new to me, so I’m approaching the review as an (almost) entirely new player. Some of our readers have probably played Myst before, either the original or the remaster on PC from 2000. I’ll also be diving into the game’s overall implementation on VR headsets.

Gameplay

I remember only brief glimpses of Myst as a kid in the ’90s. I would quizzically peer over my mom’s shoulder, not really knowing what the hell was going on as she worked her way through the game’s many puzzles on her home office desktop. Eventually I got into puzzle adventures with Riven (1997), the sequel to Myst, but only after I got my own computer and my brain was decidedly less mushy and stupid.

I was 10 years old when I first, and probably last saw Myst in the flesh. My mom admits she never finished it; she was too busy writing novels and trying to not go insane from the constant moving around the country with two rambunctious kids in tow, a built-in feature of my dad’s former life as an officer in the US Air Force. My nostalgia for Myst is pretty surface level, since I never actually played the game and only have fleeting memories of spaceships, switches, and two fantastical brothers locked inside books who would shout at you. They didn’t seem very nice.

Forget the nostalgia though. Playing the new Myst on Quest feels a bit like teleporting inside a giant mechanical clock that someone’s intentionally broken, and then filled with scraps of paper on how to fix it. You can’t break the clock any worse than it’s already been broken by fiddling with its gears, but you can’t fix it that way either. You need to look everywhere and write down clues. If you’re looking for a new challenge, the new Myst also lets you randomize puzzle solutions.

For a modern game, sometimes the linearity of Myst’s puzzles seems positively obtuse though: find a hidden note to find a hidden code to push a button to reveal a lock to open a door. It’s no more difficult than assembling an IKEA shelf—lose a plastic widget though, and you’ll be stuck in an infinite loop of despair until you can find it, slot it into place, and continue on your journey. That’s not to say that all puzzles are like that. A few are genuinely cool and make you think.

But in many cases, puzzles can be (putting it mildly) less than fun at times for new players. I can see how nostalgia may fill the gaps for anyone who wants to experience it all over again though, but in the plush, interactive environment of real-time graphics.

However fastidious, there’s still something to Myst, and even more so now that it’s in VR. In an age of constant voice overs and omnipresent ‘helpful’ NPCs telling you where to go next, I found the old school approach to game design to be surprisingly refreshing on some level, and actually more immersive at points. I was alone—truly alone—and if I wanted to get off this damn island, I would have to dig deep and do something I normally hate to do in games: read and pay close attention.

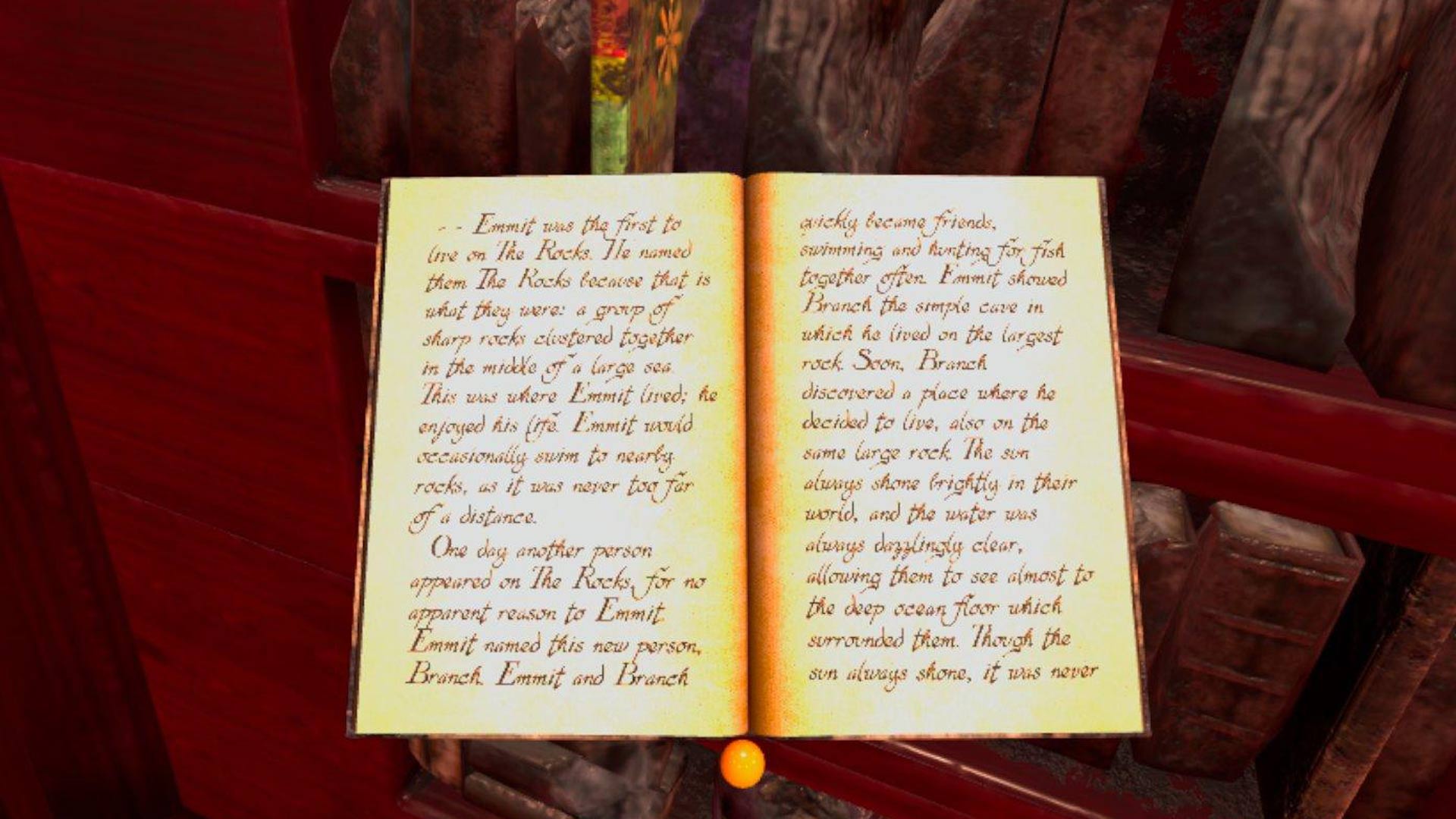

Reading in the game is actually a pretty natural experience, making books more like real objects that draw in your curiosity than on-screen manuals that you mechanically click through until you get to the good bits. A central library houses all of the game’s books, which does some of the heavy lifting in terms of world building. And the books aren’t written guides as such; some have clues and diagrams and some just tell the story of the benevolent Atrus and his two boys, Sirrus and Achenar.

Without spoiling the plot, his kids are rotten turds in their own special ways. Locked inside their own books inside the library, you have to complete each of the game’s four worlds (called ‘Ages’) to retrieve pages from each of their books. Who should you release with the final set of pages? Well, that’s up to you. There’s four different endings based on your last choice, and you can save whenever you want to experience them all.

Despite the interesting environments, sometimes fun puzzles, and the game’s pedigree as a pioneer in the space, there’s still a few things that don’t translate to VR, or any modern gaming platform for that matter.

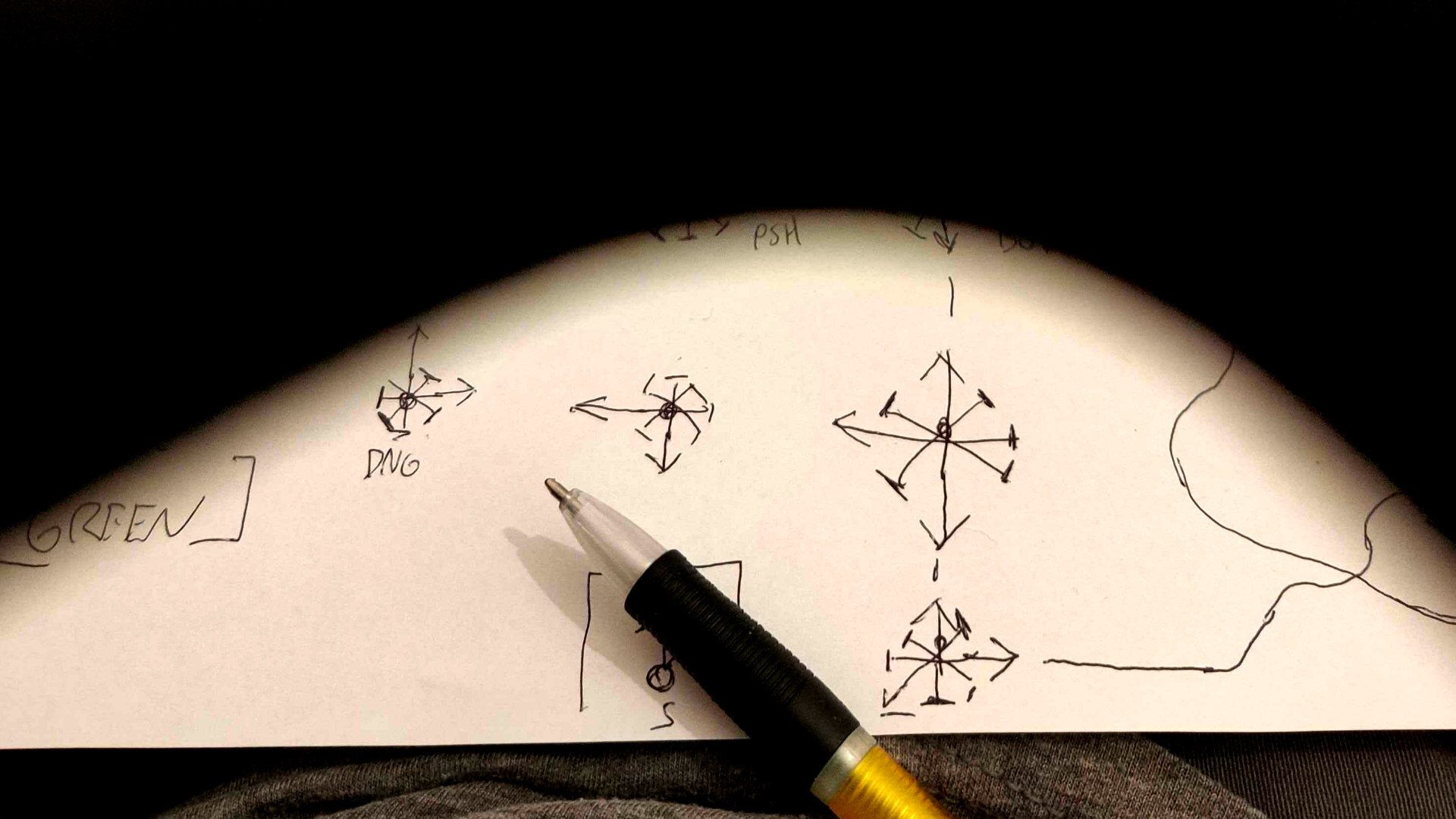

A few of the puzzles are obviously based on trial and error, requiring you to write down every time you’ve found yourself in a dead end. That’s infuriating, and even more so when you’re desperately trying to stay in-headset so you don’t break the delicate spell of immersion. More on that below.

In all, it took me around eight hours to complete Myst, with another hour spent experiencing all of the different endings, and going back to prod around gadgets for Easter eggs or alternate solutions (there don’t seem to be any). I have mixed impressions of Myst. Some puzzles are great, some are infuriating time-wasters built to test your resolve.

Immersion

One of the biggest things you’ll notice is how the world has been rebuilt for real-time gameplay. You can physically pick up books, pull levers, and slide open doors. Object interaction is really very basic though; your hand disappears when you grip an object, becoming an orange orb that only returns to its grey plastic mitt when you’ve released something. Physical objects also magically snap back to their anchored location when you let go of them, which is understandable, if not a bit immersion-breaking when you just want to switch a book or note between hands.

Keeping close to the source material, there aren’t any other beings inside the world besides a few errant butterflies flapping around back at Myst though. Since it’s pretty barren in terms of complex animations, it feels like Cyan had a good overhead to keep things looking nice on Quest. It’s a bit sterile, but for a remake it’s particularly well done.

But like the original, there’s still no real inventory or way to take notes in-game, which seems counterintuitive given the player’s physical agency in VR. Cyan says they’re adding an in-game note-taking feature soon—but for now, you’ll be stuck going about decoding the game’s complex puzzles with old fashioned pen and paper. Nose gap, be praised.

You can take snapshots of clues using Quest’s native system-wide camera tool, but you’ll have to constantly pop out of the game to scroll through your library: a real pain in the ass in terms of immersion. Unless the game lets you draw with virtual pen and paper in the upcoming update, you’ll still need the real thing when it comes to the Selenitic Age, which houses the worst, most pointless maze in the game.

One of the shining moments in Myst though is the game’s sound design. In puzzles that work with running water, positional audio is key to keeping you on the right pathway, as you follow successive networks of pipes around the map. It also lets you know when a far-off mechanism was tripped correctly, and in which direction you may find it.

Comfort

Myst features both variable snap-turn and smooth turning. You can also toggle smooth forward locomotion and teleportation on the fly, which can be helpful when ascending winding staircases, which normally make me queasy. There aren’t any vomit-inducing rides to worry about either, so Myst can be a very comfortable experience.

That said, you’ll probably find yourself running at full clip from one clue to the next, or running back to a switch you forgot to put to head on to the next level. The game’s walking speed feels a tad too slow, and its running speed a tad too fast for comfort.

Thankfully, Myst can be played either seated or standing, as it includes and both an auto height detection feature and manual adjustment to keep you where you need to be.