While Palmer Luckey provided his own Magic Leap One headset to iFixit for their tear down, the founder of Oculus certainly had his chance for a proper review before the spudgers and screwdrivers came out, and he isn’t pulling any punches either. According to Luckey, the company’s much awaited AR headset is “a tragedy in the classical sense.”

Posting on his personal blog, Luckey is critical about the overall usability of the headset, calling it “less of a functional developer kit and more of a flashy hype vehicle that almost nobody can actually use in a meaningful way, and many of their design decisions seem to be driven by that reality.”

First the good, then the bad (as determined by Luckey).

Giving the Lightpack computing unit an “A+,” Luckey was fairly happy with the design decision to keep the guts of the computer off the user’s head, which could easily cause fatigue on neck muscles if the creators weren’t careful.

The robustness of the cables was also a positive point. While he admits Magic Leap should have made the battery replaceable, he maintains “nobody is going to use their ML1 long enough for that to matter to anyone but collectors with an aim to preserve the history of AR and VR.”

Biting. Prophetic. Very Palmer Luckey.

The “Tragic”

The headset, dubbed ‘Lightwear’, doesn’t use such a unique display system as previously touted by the company, Luckey says. As evidenced by the iFixit tear down, Lightwear uses a standard AR display technology called waveguides, which are then paired with reflective sequential-color LCOS displays and LED illumination. So Magic Leap One offers a few things more than HoloLens, but only just.

One of the headset’s goals was to solve the vergence-accommodation conflict, a fact of current mono-focal displays with fixed render distances. If you want to learn more about it, check out our primer here. To do this, Lightwear’s optics offers two focal planes, which doesn’t entirely solve the issue, Luckey says. “Mismatch occurs at all other depths. In much the same way, a broken clock displays the correct time twice a day.”

Tracking, image quality, and environmental meshing, or scanning the room for 3D geometry, are all acceptable, he says.

“Have you seen Hololens? Think that, but with slightly larger FOV. The rainbow artifacts are a bit worse owing to the large number of stacked waveguides and the black levels are a bit better, but Magic Leap is playing in the ballpark as everyone else. Despite drawing enough power to keep the headset nice and toasty (seriously, it is hard to touch the magnesium shell if you are in a warm room), the display is far too dim to use outdoors. That is a shame, since the transparency is about the same as a pair of dark sunglasses – not exactly indoor material. How does the eye-tracking work? Impossible to say, because nothing uses it. That is not a great indicator.”

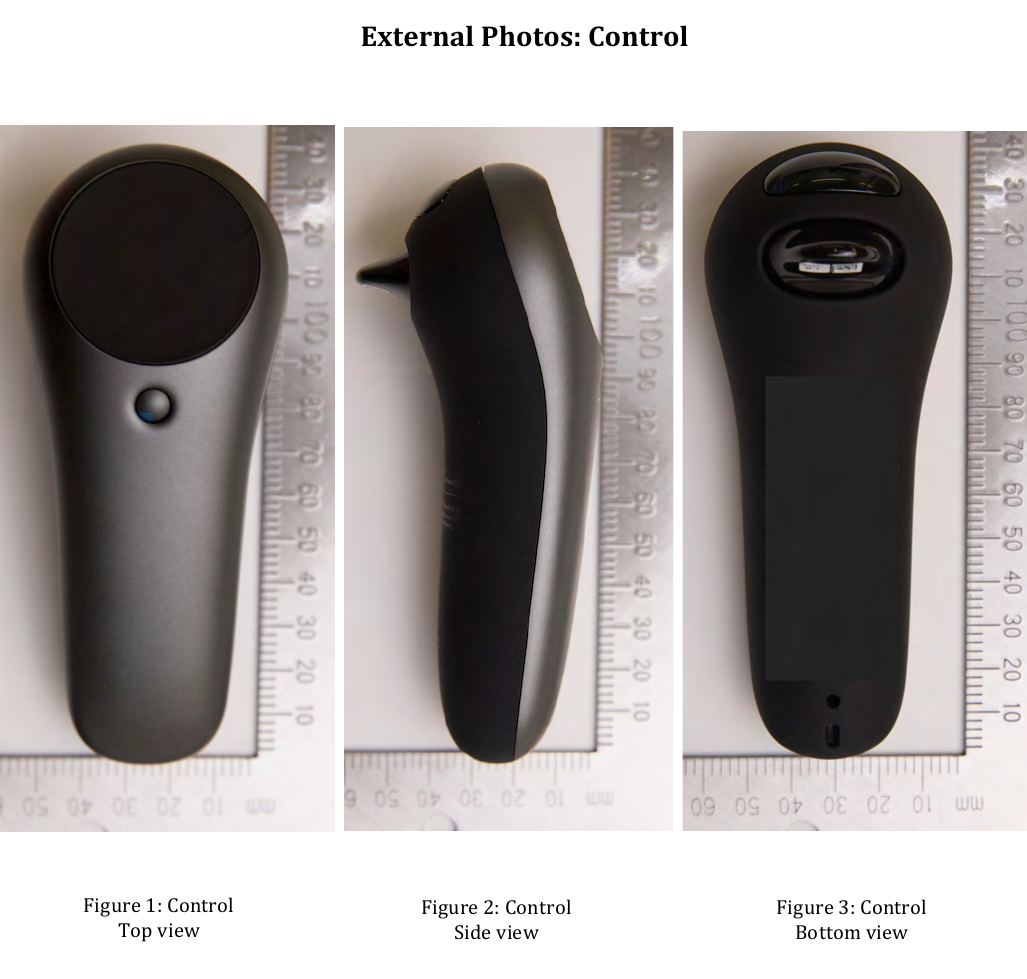

Luckey mentions the system’s controller, dubbed ‘Control’, is plainly “bad,” and that it suffers from interference from ferrous materials like those often found in industrial environments.

The lack of click-able touchpad is also a sore spot for Luckey, as he raises doubts about precision UI-selection due to having to either tap the touchpad or use the trigger for selection, two movements that can cause you to miss your intended target. Counterbalances to Control’s magnetic transmitter, Luckey maintains, help give it a premium feel, but isn’t suited for long-term use due to the weightiness of the controller.

As for the operating system, called LuminOS, Luckey posits it “is actually just Android with custom stuff on top, the same approach most people take when they want to claim they have built a whole operating system.” The UI is dominated by flat windows, something he calls “some of the worst parts of phone UI slammed into some of the most gimmicky parts of VR UI, and I hope developers create better stuff in the near future.”

Dev Kit or Expensive Prototype?

According to his own data gathering, Luckey estimates Magic Leap only sold around 2,000 units in the first week of sales, with “well under 3,000 units” as of this writing.

If true, this doesn’t bode well for the platform’s developers, as hardware adoption is somewhat of a self-fulfilling prophesy; if a company doesn’t motivate enough developers to create apps for a device, very few apps will exist and no one will buy the headset, meaning less developers are interested in the future and the platform essentially peters out as developers move on to more lucrative projects.

“Magic Leap needed to really blow people away to justify the last few years. The product they put out is reasonably solid, but is nowhere close to what they had hyped up, and has several flaws that prevent it from becoming a broadly useful tool for development of AR applications. That is not good for the XR industry. It is slightly better than Hololens in some ways, slightly worse in others, and generally a small step past what was state of the art three years ago – this is more Hololens 1.1 than Consumer AR 1.0. Consumer AR can’t happen without advancement, and it seems those advancements will be coming from other companies. There is, of course, a chance that Magic Leap is sandbagging us; maybe the real deal is just behind the next curtain! Past experience suggests otherwise…”

When it comes to revolution-launching developer kits, Luckey has some room to speak here. The Oculus Rift Developer Kit 1, the VR headset that started it all when it was released in 2013, only cost $300—a smidgen cheaper than Magic Leap One’s $2,300 price tag.

That said, Magic Leap still likely has enough funding to weather a less than resounding first product launch, although the true consumer generation offering will need to not only beat the upcoming the second gen HoloLens in terms of unique selling proposition, but also present a price-point that’s more accessible to early adopters looking to finally meet that big whale in the gymnasium—or at least a 4:3 window of it.