Penrose Studios’ latest VR film work, Arden’s Wake: The Prologue, has debuted at TriBeCa Film Festival’s Virtual Arcade. As “Prologue” implies, Arden’s Wake will be released in episodic form, though the final number of ‘episodes’ in the series, as well as whether or not Penrose might have other stories to tell in the world of Arden’s Wake, has yet to be decided, according to the project’s director and Penrose founder and CEO Eugene Chung.

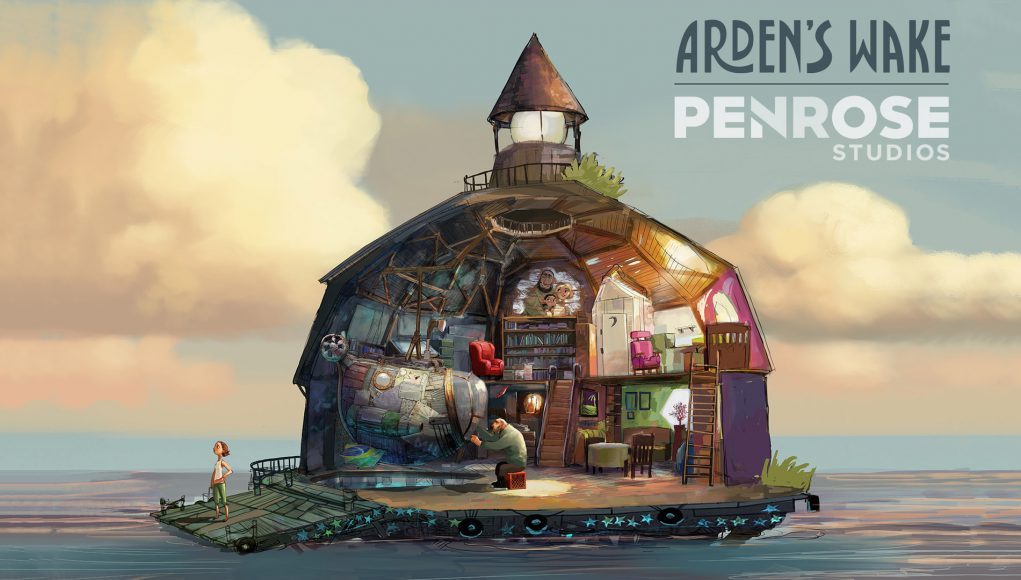

Arden’s Wake is the story of a young woman and her father living a ‘post-apocalyptic’ world in which sea levels have risen disastrously. The Prologue doesn’t answer, or explicitly ask, the why and how of the Water World (1995)-scale flooding, but instead introduces the viewer to the protagonists, their lighthouse-home, and the depths beneath them.

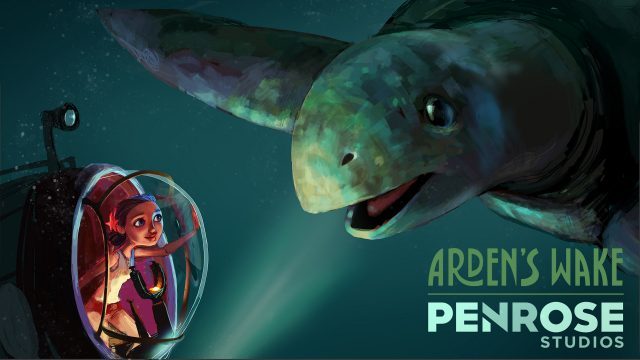

And Arden’s Wake is about depths. The heroine plumbs an ocean’s after her father’s disappearance; the user tests the depth of immersion and presence Penrose Studios has managed; and depth itself serves as metaphor and metric for what the present does and is in relation to the past. From an underwater opening sequence depicting an archetypically tragic, formative event for the heroine and her father, the user surfaces on a serene present. And it is apparent from this early juncture that the story’s action, and everything frightening or wondrous, will occur after the protagonists return to the depths.

Above the water we see what this father and daughter have made of their time in their cartoonishly charming, ramshackle house. Paintings and drawings of the family on the walls, some monumental. A visiting troubadour in a pontoon singing to the heroine and enduring the smack of fish thrown by the father. A submarine hovering, ready, above a portal to the sea. And books, knick-knacks, the father’s apparent alcoholism: records of lives lived. When the father disappears, suddenly, into the horizonless sea, the possibility of negotiating or otherwise navigating the depths and the very, very large things that inhabit them becomes an imperative, as does reconciling precisely what the family’s life and home have been built upon.

The reader may be privy to videos and images depicting the tearful reactions wrought by Penrose’s last effort, the lauded twenty-minute Alumette. Fifteen-minute Arden’s Wake tweaks that work’s animation style (less stop-motion) but retains many of its mechanics. Want to see what’s going on inside the heroine’s cabin? Exploit the 6DoF and push your head through walls. Want to ignore the father and daughter’s interactions entirely and stand outside the house staring blankly at the horizon? By all means. Even the focus on primary attachments—mother-daugher in Alumette, father-daughter in Arden’s Wake—remains.

The mechanics underpinning Arden’s Wake’s production, however, are markedly different from Alumette’s. Penrose’s Chief Scientist Jimmy Maidens has developed a number of tools, including what the company is calling ‘Maestro’, a “social VR creation tool that allows [Penrose] to collaborate inside a fully virtual space.”

Chung semi-jokingly described it to me as a “proprietary Penrose tool in the proprietary Penrose tool suite.” Whatever else it is, Maestro is fun. The team and I, each member represented by a rudimentary, if strangely cute, circular face and blocky hands, donned Oculus rigs and flew around a paused scene from Arden’s Wake, while animator Bruna Berford demonstrated how to leave and export comments about animations and set design. By all accounts the effect has been to drastically expedite production time.

This is something to be thankful for. Impressive as Arden’s Wake undeniably is, I wanted more: more plot, more character development, more of the universe Penrose has begun to build. If The Prologue proves anything, it’s that Penrose could produce an episode twice as long without exhausting the viewer. Maestro ought allow them to churn it out.