A new type of haptic sonar glove developed by Ph.D. candidates Aisen Carolina Chacin and Takeshi Ozu of the Empowerment Informatics program at Tsukuba University in Japan, lets the user “feel” underwater object using a mix of SONAR echolocation and ingenious water jets for feedback.

We’ve seen a few unusual peripherals in our time here at Road to VR, but this new glove from Ph.D. candidates Aisen Carolina Chacin and Takeshi Ozu of the Empowerment Informatics program at Tsukuba University are something else.

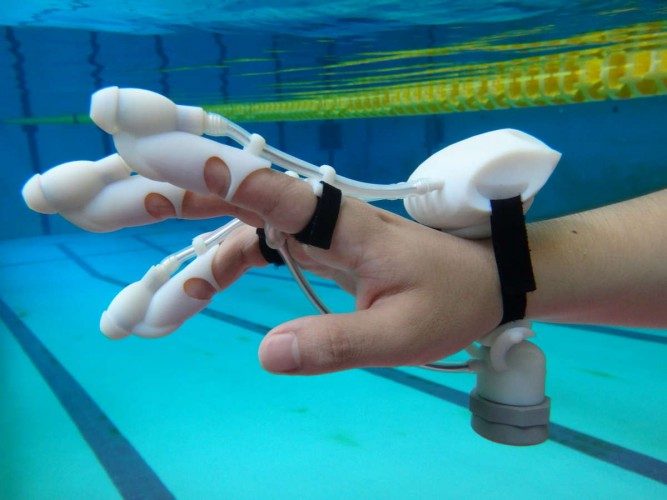

The design brief was to devise a device to help with the discovery and location of underwater objects, sometimes deep under the surface, one that provides instant and intuitive feedback for the person using it. The team came up with IrukaTact (iruka means ‘dolphin’ in Japanese), a glove that incorporates a wrist mounted SONAR device which, using echolocation techniques, can map and pinpoint submerged points of interest or locations. The object location data is then translated into haptic feedback to the wearer using an ingenious series of water jets fed through the fingers.

“Our overall goal was to expand haptics,” says Chacin, speaking to Popular Science. “How can you feel different textures or sense depth without actually touching the object? Vibration alone doesn’t cut it for me, or most people, for that matter.”

The glove form factor means that, objects potentially unseeable by the naked eye underwater, can be grasped by the wearer once the haptic vibrations are felt.

Popular Science go on to describe the technical makeup of the glove, also noting the possibility for it to be paired with VR headset, like the Oculus Rift:

The glove uses a MaxBotix MB7066 sonar sensor, three small motors, and an Arduino Pro Mini, and is programmed to send signals to the three middle fingers in silicone thimbles. The motors are placed on top of the index, middle, and ring fingers, and pump water from the surrounding environment. This water is siphoned onto the wearer’s fingertips to create pressure feedback. The thumb and pinky are left free in order to reduce clunkiness, save battery power, and improve movement. A silicone ring around the middle finger, connected to the sensor at the wrist by a small tube encasing the sensor’s wires, keeps the sensor parallel with the hand and allows it to read information from the direction the palm is facing. The sensor can receive and send signals from up to 2 feet of distance underwater, though Chacin says in the future it’d be possible to expand this range.

Of course, the idea of carting a VR capable laptop and most certainly ‘un waterproof’ VR headset to a dive site, is probably less than attractive, but the method of providing haptics in this way are interesting nonetheless.