Noah Nelson (@noahjnelson) is the head writer of Turnstyle News, a public media website that covers tech and entertainment, and a project of the Peabody Award winning Youth Radio.

Noah Nelson (@noahjnelson) is the head writer of Turnstyle News, a public media website that covers tech and entertainment, and a project of the Peabody Award winning Youth Radio.

Last week I had the privilege of seeing a number of cinematic experiences that were made specifically for VR. The first set was part of the launch party for the new Nokia OZO VR camera. Later in the week I got a preview of one of the films that will be on display at the Slamdance Film Festival this January. Between these two experiences I learned a hell of a lot about both the state of the art in VR filmmaking and just where this whole thing might be going.

See Also: Nokia’s ‘OZO’ VR Camera Pre-orders for $60,000, Shipping in Q1 2016

Most interesting, perhaps, are the things I saw which challenged the conventional wisdom about 360 filmmaking. Let’s start there.

Editing for VR Cinema

At the Nokia event I saw a piece called The Mutiny, which was produced by New Deal Studios. New Deal is no stranger to 360 film, having worked previously with Jaunt about a year ago on the still unreleased The Mission VR. The director of both of those pieces is one of New Deal’s co-founders—Matt Gratzner—who a year ago made a statement that I found hard to believe.

Gratzner, speaking at a VRLA gathering held at New Deal Studios, put it out there that it was possible to have cuts—regular edits—in a 360 film.

At the time this idea was considered impossible. Every other filmmaker I’d spoken with accepted it as a given that cuts were too disorienting in VR. Cross fades, wipes, and dissolves were all fine but to make a jumpcut was too much for a viewer to handle. It’s taken me almost a year to get to see visual proof of what Gratzner was talking about. I am pleased to report that he is correct, although the cuts seem to need to be executed in a very specific way in order to work.

It goes a little like this.

The Mutiny showcases a fight between two pirates. One pirate knocks the other down, and then the scene shifts to a different angle on that knocked down pirate. The catch is that the knocked down pirate stays in the same place relative to where they were in the previous shot. It’s the world around them that rotates.

Try this out: hold up a pen in your left hand. Extend your arm out about half as far as it can and then line the pen up so that it is just to the left of the center of your vision. This pen represents the knocked down the pirate. Look at the pen directly. Now take your head and move it slightly to the right but keep your eyes on the pen. That parallax behind the pen—the world moving behind it—is all your brain has to adjust for. But because your attention is fixed on the pen you don’t notice it as much.

What is true for the pen is true for the pirate.

This may not seem like much, but the ability to move the camera—to jump in terms of angles or time—is a critical tool in the filmmaker’s belt. Until I saw this it seemed obvious to me that the disorientation that came with a cut far outweighed any narrative advantage provided by the shift. While this technique isn’t a panacea, and it is certainly more restrictive than your usual edits, it opens up far more parts of the palette then we had before.

Intellectually speaking, what’s most interesting is that it’s the fixation on an object that enables the cut in the first place. It reminds me that one of the first major milestones in childhood development is the infant brain being able to deal with the concept of object permanence. There are ramifications beyond the edit here in terms of what can be done narratively with VR when storytellers stop thinking about framed images and start thinking about the objects within a field.

The Field of View

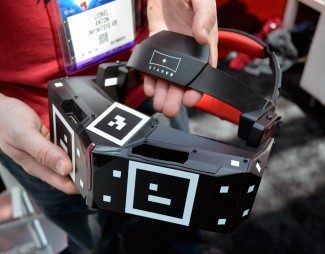

The other big revelation of the night with Nokia was my first experience of Starbreeze’s StarVR headset. I got to try it out with The Mutiny after I had already seen that piece on the Oculus Rift Crescent Bay prototype.

You’ve probably heard, if you have been lucky enough to experience it yourself, that the field of view on the Star VR is ridiculous. When I had to explain this to people who are new to VR headsets I hold a phone in front of their face. “That’s what a regular VR screen is like,” I tell them. Then I slide phone to the side and tilt it back towards their head, so that one end is at their nose and the other is headed towards their ear. “That’s what the Star is like.”

You can, of course, try this at home.

The added field of view is like upgrading from a 4:3 to a 16:9 screen. Or from Academy aspect straight into IMAX. No longer does the viewer need to move her head in order to catch what’s going on around her. Instead she can just move her eyes. You know, the way we normally look at things.

This opens up possibilities for how filmmakers can stage action, but it also creates a set of limitations. Namely, if a filmmaker doesn’t know what headset their content is going to be viewed on then they can’t stage scenes to maximum effect. On StarVR the action in The Mutiny seemed much tinier here then it did on the Crescent Bay. This is because the action didn’t fill the frame on the StarVR.

Now I know it seems crazy to talk about filling the frame when the user has control of where the camera is looking, but the dance here is between where the filmmaker wants the user to look and what the whole scene is doing in order to shepherd the user’s attention. This elasticity of attention is the key differentiator between VR filmmaking and regular filmmaking.

(And I’m sorry if you prefer 360 filmmaking, I like to use them interchangeably. When we get far enough down the line most of what we see will just be procedurally-generated photorealistic images based on motion captured actors. Most people won’t be able to tell the difference between that and something “filmed” with a light field device. That day can’t get here soon enough for me, so in the meanwhile just let an old man call it what he wants.)

Knowing where the bounding box of that elasticity ends—how far apart you can space actors and still have them be within a viewers field of vision—is critical. Otherwise you might as well be directing with a pillow over your head while small children hit you with plastic baseball bats. But if you do know how big that frame is, then you can start to play with what happens at the edges of it. You can toy with the attention of the viewer: leading them. Misdirecting them. Surprising them.

The Rubber Band

Let’s stay with this idea about how far apart you can place the actors. Because the key thing about staging a theatrical piece—and let’s be clear that VR cinema is a hell of a lot more like putting on a stage show than it is shooting a film—is creating dramatic tension in physical space between actors.

Some of this is dependent on the skill of the actors and how they play off each other emotionally, but another component is in the skill of the director. How good is the director at placing two or more people—or a person and an object—in relation to each other in such a way that it triggers dramatic tension?

I got to see some rather clever minds working on this issue on another VR film, The Visitor. This is a piece that will be featured at Slamdance’s first Digital Interactive Gaming showcase.

Now there are no cuts in The Visitor. And unfortunately I wasn’t able to hear the dialogue of the piece because of the gallery setting where we viewed the preview. It was just too loud in that room. But that meant that I experienced the short film as a silent film, which allowed me to focus on both the design elements and the relationship of the actors to each other and the set.

Now the genius thing that the filmmakers—James Kaelan, Eve M. Cohen, and Blessing Yen—did was that they put the ‘rear’ of the camera with its back right against the point where two walls converge. This meant that after doing the requisite looking around behind me I knew that there was little chance of something emerging from directly behind my head.

At fade-in, a man stood in front of me, slightly to the left, and a woman stood to my right. If I were to reach out my hands towards both of them my arms would form a 90° angle. This caused me to look back and forth between the two because the bounding box of the Gear VR is small enough that they were both just at the edge of my peripheral vision. This is the filmmakers playing with the bounding box. And here it works pretty damn well. At least for starters.

Now, remembering that I had the handicap of not being able to hear the dialogue, I began to favor the male actor to my left. For most of the piece he was physically closer to me than the female actor was. In theatre-speak he was downstage and she was upstage and every theatre director will tell you that the downstage actor usually has primacy. (Fun fact: upstaging someone is when an actor moves upstage, forcing another actor to turn their back on the audience, and thus turn their focus on the upstage actor.)

However, the image of the woman was more interesting than that of the man. She was reflected multiple times between a ceiling mirror and a glass tabletop which reflected the ceiling reflection. Not quite an infinity effect, but fascinating nonetheless. But the proximity of the male actor led me, perhaps because of the lack of sound, to keep coming back to him.

With a wider field of view this may have been less of an issue. I could have flicked my eyes back and forth between the two in StarVR. But I find it interesting that what was foregrounded became more of my focus than that which was moving. I doubt this is a universal for all users, but I can’t help but think that distance from the observation point of the active agents in a scene plays a part in the calculus of attention.

I will also say this about The Visitor: it proves without a shadow of a doubt that a fantastic setting is worth the time spent both for the user and for the scouting team that finds it (or the construction crew who builds it). Not only because it gives you something interesting to look at for every second you are inside the experience, but because it inspires directors to more dynamically use space.

Finally (No, But Really, Finally)

This one has been long, and I hope it gives you a lot to think about as we move into the holiday.

I know that there are luminaries of film out there—honored figures like Pixar’s Ed Catmull—who are doubting whether or not VR will ever be a medium for storytelling.

To that I say look to gaming. Video games at their narrative best are not linear narratives, but they contain linear narratives within them in order to build more complex interactive and non-linear narratives. You need search no farther than this year’s Rise of the Tomb Raider (2015) to see what I’m talking about. Like games, the pinnacle of VR storytelling is going to include but transcend linear narrative limitations. Some will accomplish this by providing great agency to the viewer in terms of narrative choices, and others will do so by layering the worlds in which the story takes place with telling details that suggest greater complexities than what is readable at first glance.

Truly great storytelling—whether it is in novel, comic, or film form—already does this. I believe that in order to make the time spent ‘within the Rift’ worthwhile, VR storytelling has to do this from the get-go.

We’re not there yet, but then again it took 46 years between the Lumiere brother’s first film screenings and when Citizen Kane made it to the movie house. I doubt we’ll have to wait that long for a VR story to come along and show us all how it’s supposed to be done.