Having started production on its first title even before the original Oculus Rift DK1 development kit was sent to developers, Canada-based Cloudhead Games is one of the world’s most veteran game studios dedicated to virtual reality. The studio has staked its very existence on its ability to build compelling VR games. With three prior games under its belt, Cloudhead poured its hard-won expertise into its latest, Pistol Whip, which has propelled the studio new levels of success.

The 2016 launch of Cloudhead’s first game, The Gallery – Episode 1: Call of the Starseed couldn’t have been under more ideal conditions. The studio was among a handful of developers which received access to early to HTC Vive development hardware, allowing the game to launch side-by-side with the headset. Call of the Starseed was lauded and promoted at the launch of the Vive by Valve and HTC as one of the first VR titles to take true advantage of VR’s capabilities.

Critics praised Call of the Starseed’s polish and scope as a departure from other early VR titles which felt more like demo games. In the following years, Call of the Starseed and its sequel, Episode 2: Heart of the Emberstone (2017), would see regular mentions in discussions of top VR games.

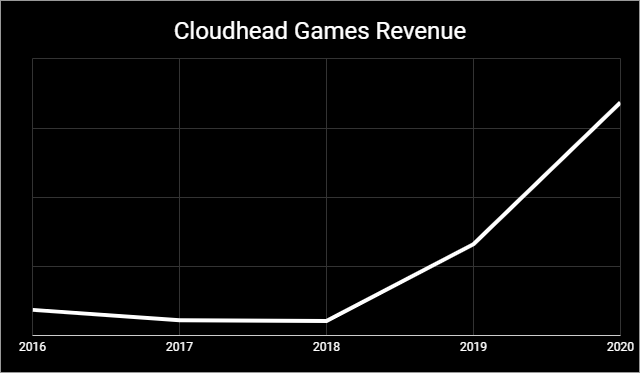

Despite the praise and momentum, the success of Cloudhead’s latest title, Pistol Whip (2019), has positively dwarfed what the studio earned from its early entries in VR.

On top of this exclusive look at the studio’s relative revenue, Cloudhead also shared that its sales in December 2020 were up 60% over December 2019. Further, the number of users that have played the studio’s games increased by 131% from 2019 to 2020.

Cloudhead CEO Denny Unger tells Road to VR that Pistol Whip’s success has come from both by a growing VR market and a major pivot in the studio’s approach to VR design, which was driven by Cloudhead’s hard-won VR expertise and the frightening state of VR in 2018—when the studio came uncomfortably close to being forced to abandon VR altogether.

The Storm

“2018 was a really terrible year for VR. Most of the major OEMs were waffling on what they were going to do, the numbers weren’t great, a lot of our peers were closing up shop… no one was giving money for projects… investors weren’t investing,” Unger said. “There was a bunch of things happening in 2018 that were really dire for VR. The growth was really, painfully slow. That also coincided with a bunch of decision making about what our next project would be.”

“We had a really short [financial] runway at that time and we had to look at what was working on market. We knew it had to be accessible. It had to be really easy to share and compete with friends. You had to look good while playing it—we thought about how influences would look while playing it. It had to have high replayability, it needed to be a games-as-a-service model, and, really importantly, it had to be targeted toward the Quest.”

Pistol Whip was thus conceived and launched, at a pivotal moment for Cloudhead and the industry as a whole.

“At this time we knew three things: we knew Quest was coming, we knew that Valve Index was coming, and we knew that Half-Life: Alyx was coming. […] if those three things did not drive a turning point in the VR market, then nothing would. And at that point then we would have to pivot away from VR.”

The turning point the studio was betting on finally came, largely driven by Quest in 2019 and bolstered further still by Quest 2 in 2020. In relatively short order, the studio has gone from staring down the end of its financial runway to laying down strategic plans years into the future.

“This, to me, is definitely a turning point in the market—a serious one—this is not a ‘maybe’ thing. It’s the first time, over the last eight years, that […] we’re now profitable to the degree that I can confidently say that we’re gonna be here for a few years,” Unger said. “And we’re a 25 person studio—that’s no small thing—I don’t actually think many VR studios can say that. We don’t have VC funding, we don’t have a board of directors, we’re completely running on our own steam. A big portion of [this success] is coming from the Quest market.”

Cracking the Code

A growing market is great news for all VR developers, but few apps are seeing Pistol Whip levels of success. What’s different about it?

“Retention and time played have both been really important metrics [for Pistol Whip], and we’ve seen massive spikes in that with Quest and Quest 2. People keep coming back, over and over and over again,” said Unger. “[…] Oculus made a point of letting us know how amazing that specific aspect to our game was, that it just has this really sticky quality that keeps people playing, and that it’s not slowing down.”

Compared to The Gallery, Pistol Whip is a radically different kind of game. Rather than a linear narrative adventure, Pistol Whip is a replayable shoot’em up which couldn’t be easier to pick up and play. Unger said that while Cloudhead still has ambitions to build the third episode of The Gallery, Pistol Whip was built for the needs of the VR market as it exists today.

In deciding on the pivot, the studio reasoned that the breakdown of consumer interest in various genres—shooters, platformers, simulation, strategy, narrative adventure, etc—is roughly the same in VR as it is outside of VR. So to build a VR game in a genre that’s already niche outside of VR would be building a niche in a niche—not a recipe for success.

That meant setting aside the narrative adventure of The Gallery, and picking something with wider appeal. At the same time, the studio made a conscious choice to focus on ease of use.

“[…] one of the pillars for Pistol Whip was that we want to engage the ‘lizard brain’—the reactive mind. Not the mind that has to be deeply analytical about things. And the way we do that is we put you in a situation that’s threatening, and you just react. So there’s a lot of movement that happens in Pistol Whip—physical movement—that’s just driven by these underlying subconscious systems,” Unger said. “And that was a really important breakthrough for us. Like, ‘how do we tease out people moving or behaving in this specific way’ without them even having to think about it? And I think that’s where players get a lot of enjoyment out of Pistol Whip, because they’re active, they’re moving around in the environment, and they’re only focused on shooting and survival.”

Interestingly, the realization that ease-of-use should be a key pillar actually came from fizzled business pitches between Cloudhead and Hollywood studios.

“[Development of Pistol Whip] came off the tail of doing—god I don’t even know how many—pitches with Hollywood. They were really desperately trying to wrap their heads around how they could utilize VR,” said Unger. “[…] even though most of those things fell apart—and Hollywood kind of dropped the ball on VR in general—the benefit of doing that exercise for us was that we really had to ask ourselves some tough questions about how complicated you can really make a VR experience for Joe Blow consumer. And that led us to some assumptions about about what we had to nail on Pistol Whip.”

One of those tough questions was how the game should handle locomotion. While The Gallery, and plenty of other VR games, have ported basic stick-based movement from the non-VR games that came before, Cloudhead had other plans for Pistol Whip.

“[…] one of [our key lessons] was recognizing […] that actually locomotion is something that kind of needs to ‘go away’ in VR. And I don’t mean that you stand in a room and just stand there—that’s not what I’m talking about. The cognitive load of thinking about how you have to move needs to go away,” said Unger. “[…] It should still happen in an experience, but you need to totally remove that cognitive load from the user so they can focus on the other things they’re doing in the virtual environment.”

The same concept of ‘low cognitive load’ carried into the game’s interaction design too.

“[…] this is a bit old school but, in a way I don’t like that there’s so many buttons on modern VR controllers. I actually appreciated the [trackpad on the original Vive controllers] because it forced designers to think more VR-centric… like ‘how do I make my hands do the thing in the experience [instead of using a button]’? For me it’s going back to simplified input. Again, the user shouldn’t have to think about how to do a thing. It should just be a natural organic thing that they already know how to do.”