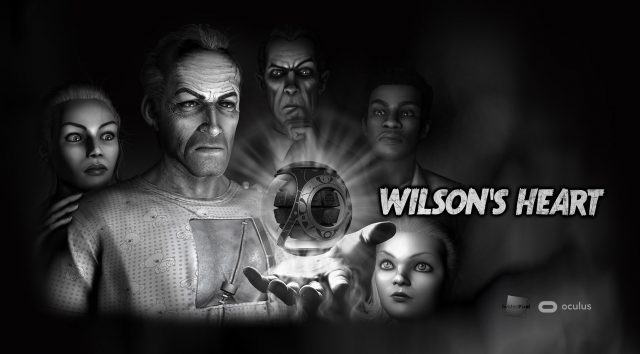

Wilson’s Heart (2017) is a psychological thriller that takes you on a wild first-person adventure through the mind of a hospital patient recovering from a curious surgery, one that has replaced his live-beating heart with a strange machine. Ripping it from your chest, you find it gives you a growing number of abilities to help you not only fight against your personal demons, but also some very real ones that have passed into the world thanks to experiments done by the brilliant, but clearly insane Dr. Harcourt.

Wilson’s Heart Details:

Developer: Twisted Pixel Games

Publisher: Oculus Studios

Available On: Home (Oculus Touch)

Reviewed On: Oculus Touch

Release Date: April 25, 2017

Gameplay

Robert Wilson is a hard-boiled WW1 veteran who’s clearly seen some shit in the 67 years he’s walked the Earth. Voiced by actor Peter Weller (Robocop, The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension, Star Trek Into Darkness), his gravelly, steady voice is strangely assuring as you stalk down the corridors and mind-bending rooms of the abandoned hospital complex—all of which would scare the living daylights out of anyone in their right mind. But that’s the thing; you don’t really ever know if Wilson’s in his right mind, or if the whole world around him is gone topsy-turvy. And his whirring, mechanical heart is to blame.

Either way, he’s just that sort of classic tough guy you’d find in a dime novel detective story or comic book. In fact, the game is brimming with these sorts of ’40s tropes and archetypes, not to mention your standard selection of vampires, werewolves, lagoon monsters, and mad scientists ripped straight from the silver screen. Being rendered in black-and-white and featuring classic movies monsters might sound too campy at first blush, but the reality is Wilson’s Heart is a dirty, bloody mindfuck in all the best ways, so don’t be surprised when reality crumbles around you.

And the world of Wilson’s Heart isn’t just weird, it’s brutal too. Moving realistic-looking dead bodies to get to clues is a normal occurrence, and doing it in VR only multiplies the emotional effect. That said, jump scares happen, but they’re few and far between, leaving more room for the monsters, the bump-in-the-night atmosphere, and the supporting cast to do the scaring. Suspicious behavior from the group of survivors you meet will keep you guessing as to who’s on your side.

Because the adventure genre is usually heavy on narrative and scripted action, but tends to deemphasize combat, the fight sequences were a welcome bonus at first, adding more danger to an already skin-crawling universe. And while Wilson’s Heart is one of the most visually impressive VR games to date—and I can’t emphasize enough just how truly good it looks—the world’s monsters offer lack-luster combat which can become very predictable after the first encounter. Over the course of the game, the sense of danger I felt in the beginning slowly degraded into apathy as monsters follow the same attack patterns over and over throughout. Then again, you may not be in it for the combat aspect at all, which is just fine.

[gfycat data_id=”SharpWideeyedBillygoat”]

You may be in it for the story. I finished the game in a little over 5 hours, and that was with plenty of deaths and faffing around with some of the world’s literature, however if you read every comic book, newspaper, and rustle through every drawer for clues, you could take longer. These can be informative, silly, and downright creepy as the comics slowly enter the weirdness factor that is your constantly changing reality. While playing off its patented brand of 1940s camp, dialogue is well-scripted and its phenomenal voice acting help to keep it on the modern-side of storytelling.

You may also be in it for the puzzles. Because you straddle the line between figuring out if the world is crazy or if it’s all in your demon-addled brain, puzzles become more and more surreal as you go. From turning on lights to scare away demons, to the gravity-defying act of flipping an entire room to get to a stubborn door that keeps disappearing, puzzles are usually interesting. I did however find them oddly placed, bordering on completely arbitrary. Oftentimes I would walk into a random room, find a puzzle, solve it, and leave not knowing why I had entered in the first place.

Immersion

It’s clear from the start that the developers paid lots of attention to getting characters to emote naturally and look alive—something that is more important in VR than on traditional monitors because you’re actually face-to-face with a person, and can naturally tell when something’s off. Characters in Wilson’s Heart make eye contact and seemingly talk directly to you, grounding you further in the narrative. Character design is still cartoonish though, keeping it safely out of the uncanny valley.

[gfycat data_id=”SlimParchedFruitfly”]

This leads me to my least favorite part of the game: the lack of agency. As a player, you’re constricted to node-based teleportation, meaning you only have a few choices on where to go. Walking into a room, you immediately see the hot spots for clue locations and all important drawers are highlighted, which takes away some of the joy of exploration personally.

Inconsistent object interaction also adds a layer of frustration on top of this, as one moment your mechanical heart can fly out of your hand and directly hit a demon, and the next it literally avoids an important target because the game has a better idea of what you’re supposed to do. In this regard, I kept butting my head against the game. A monster has to die in one way and one way only, because the game demands very specific interactions. And that wouldn’t be a problem if the game’s demands were consistent. Hand-to-hand combat with one enemy can differ wildly across similarly-sized enemies for seemingly no reason at all. One moment you can block a punch from a demon, and only a short while later the blocking mechanic is no longer effective. You’re then punished with death until you can find that one item in your periphery that you necessarily must use to continue on with the sequence.

And the heart. Your mechanical heart, although gifted with several abilities, will also activate in only a few ways deemed useful during a fight. Using the abilities when you’re prompted oftentimes culminates in the most cinematic death possible, but leaves zero room for player creativity.

Comfort

Because the game features node-based teleportation, and no other artificial locomotion scheme, Wilson’s Heart proves to be an exceedingly comfortable experience.

As a standing experience, the two-sensor Rift set-up is enough to get you by, as nodes tend to put you either facing the action or the object of interest, so nearly always a forward-facing experience. That said, a 3-or-more sensor set-up can certainly give you more mileage in terms of facilitating smoother object interaction and greater room-scale immersion.

Lastly, the inventory system is a simple, ‘on-rails’ experience, as important items are stuck away into the ether and later retrieved automatically when needed, so there’s no fumbling through submenus to find what you need. In fact, there are no menus, health gauges, or HUDs to distract you on your quest to retrieve your heart and escape the hospital.